We’re over an hour into Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes before we hear a human voice. That’s not to say we hear no voices; the apes here, “many generations” after the events in 2017’s War for the Planet of the Apes, have become, for them, downright chatty (though they mostly speak haltingly still, with occasional flutters of sign language). The human is Mae (Freya Allan), who is smarter than the average feral human at this stage in the Apes timeline. She throws in with some idealistic chimps in opposition to Proximus Caesar (voice of Kevin Durand), head of a more violent ape clan, who wants to get into a vault that contains lots of technology. Still, the movie privileges ape voices over the few speaking humans’.

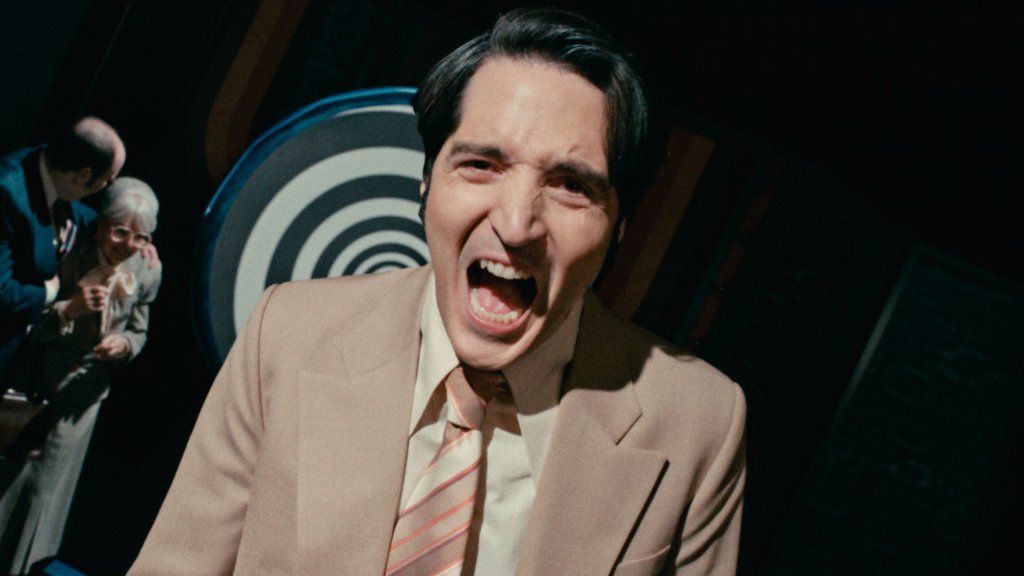

I was a major fan of the preceding three Apes films, which, with the help of Andy Serkis as Caesar, shook out as unusually insightful Hollywood blockbusters. They felt as though they mattered and had something to say — they had substance. Kingdom isn’t nearly as sharp or as full of surprising details, but it engaged me anyway. If this franchise is to go on without Caesar, telling stories about his legacy and how it is used and misused isn’t a bad way to go. Our hero here is Noa (voice of Owen Teague), member of an eagle-training clan headed by his father. Proximus and his army invade Noa’s village, kidnapping the able-bodied of his clan so they can work to open the vault. Noa, Mae and an especially bright orangutan, Raka (voice of Peter Macon), ride off to free the eagle clan and otherwise discourage Proximus’ plans.

Caesar and Serkis are missed, but the story here is sturdy enough that we get on board. It has a lot of good will from the previous films going for it, and manages to hold onto some of it. The problem is, I’m not sure how many flavors of story can be told in this universe; how many times can they reiterate the monkey-Spartacus plot? The special effects, as always, are magical — a chimp named Anaya at one point signs “Anaya is scared” and shows the most abject facial expression of misery I’ve ever seen. The work on all the apes is top-flight, enabling them to convey any emotion and all its nuances. When apes from the peaceful eagle clan are reunited with clanmates they thought dead, they respond with unfiltered joy that’s like a shot of oxygen. The apes mostly haven’t learned to be circumspect with their feelings — that’s a human thing (“echoes,” the apes call us) — though the shrewder, and more aggressive, of the primates can dissemble.

Kingdom is more interesting when alluding to details and threads that it just lets go. William H. Macy turns up as a sketchy history teacher who’s been tutoring Proximus, and I wanted to sit in on one of those classes. A short tale about what exactly a human would teach an ape about the time before, when (as acknowledged here) humans dominated and kept apes in chains, would be a good one to tell in an Apes TV episode or comic book. This teacher implores Mae to forget about the good old days and get used to the new way of things, indicating that the humans have developed opportunistic people who’ll try their luck with the apes rather than sleeping under trees. If another trilogy is planned, maybe they’ll get into the concept of human “donkeys” (the term derisively used in War for those apes who worked with the human militia).

This 56-year-old franchise seemed to run out of gas in the ‘70s, and Tim Burton’s attempt in 2001 read more like his riff on the Apes themes than a serious bid to relaunch. But the reboot series starting in 2011 found fresh and intriguing things to explore, and Andy Serkis’ virtuoso complexity as the hero seemed to lift everyone else’s game (it is, I feel, his crowning achievement in mocap acting). If we can’t have his Caesar (though in a franchise that in its second film blew up the earth and then circled back to 1970s America in its third, never say never again) and the franchise can’t just be left alone now, I suppose an Apes going concern is fine. Thoughtful writers can pursue issues in the Apes ‘verse that make comparable franchises look like pabulum, and special effects have sharpened to the degree that the world of the apes can be shaped and demolished in ways that aren’t limited by the physical world. But if they’re just going to retell the story of good and bad apes and humans fighting each other again and again, why bother?